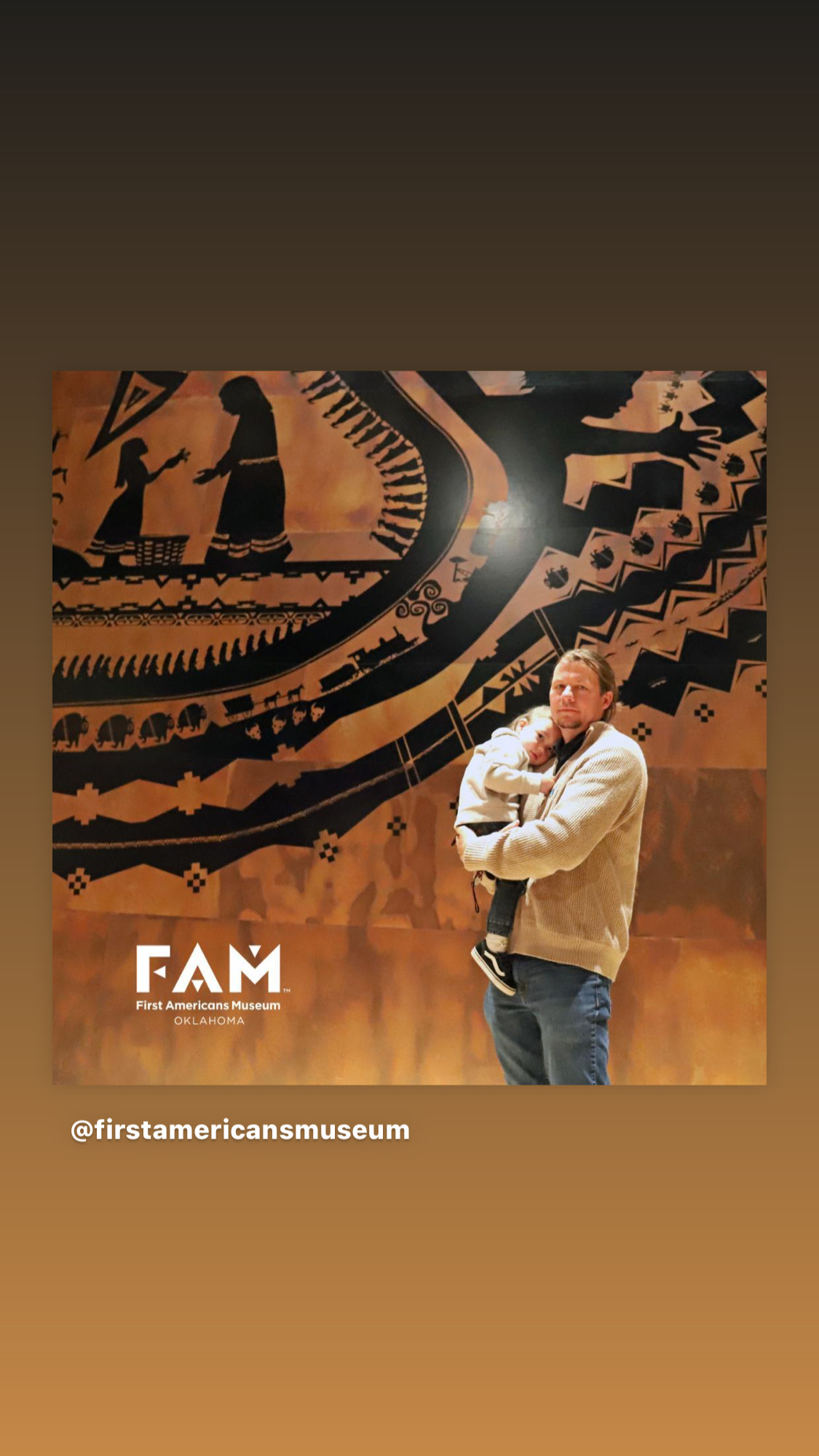

Joseph Lewis Erb and ᎠᎹᏱ Lewis Erb standing in front of the permit installation of Joseph’s work , “Indigenous Brilliants”, commissioned by the First American Museum (FAM) in Oklahoma City. FAM represents 39 tribal nations.

The History

Erb’s people – highly intelligent, literate, and wealthy – weren’t always called the Cherokee Nation.

Run by tribal town leadership, they existed since before memory, and their oral history extends back 10,000 years or longer. They had advanced cultures and rich lives before European contact and trade with European immigrants, which eventually led to their struggles to remain in their lands and hold on to their sovereign rights.

In the early 1820s, they had a written language, a newspaper published in both English and Cherokee, and a constitutional government. They went to Dartmouth College, which was originally conceived as a missionary school for Native Americans, as well as other Ivy League schools. They also played instruments.

In 1838 and 1839, Cherokees were removed by efforts of the United States government, from their homes and farmland in North Carolina, Kentucky, Tennessee, Georgia and parts of Alabama, due to racial prejudice, the growth of cotton agriculture, and the discovery of gold on Cherokee land. They were placed in stockades until their departure and forced to take a half year or more journey to land beyond Arkansas, which is now Oklahoma. About 4,000 perished out of 16,000 Cherokees forced on what is now called the “Trail of Tears.”

“Cherokees were more literate than Americans by our removal time (i.e., the time they were forced from their lands by the government after the Indian Removal Act of the 1930s, passed by President Andrew Jackson),” says Erb. “By our removal time, some estimates put Cherokees’ literacy close to having 80 to 90 percent literacy rate when Americans in that area were anywhere from 9 to 13 percent. We were possibly one of the most literate people in the world.”

But even after their removal from tribal lands, the people continued to thrive and grew into the sovereign tribal government of today – one of the largest nations in the U.S., with more than 390,000 citizens worldwide. Many still live-in northeastern Oklahoma on boundaries (they don’t call their lands reservations) that extend 7,000 miles, a place where Erb once lived and sometimes still does, a place his mom and grandparents call home as well.

“My mom’s parents’ family have been in the same community since removal, as far as being removed from our homeland,” he says.

Today there are only three continuous federally recognized Cherokee Nations, the largest in Oklahoma, with several famous people coming from these nations, including linguist Durbin Feeling and Hollywood star Will Rogers. Cherokee Nation is visible on Google maps, thanks to Erb.

"Cherokee Communication.” Copper cuff 3”x4” Private collection.

Today

Recently, Erb, a computer animator, film producer, educator, language technologist and artist, sat in front of his computer during a Zoom meeting, the image of a woman in a flowered dress in the personalized Zoom background behind him.

The Cherokee illustration was an image of his grandmother. When asked what the background was, he responded that unofficially it was for an animated series in Native language funded by a tribal nation. This is one of many projects he is working on. In fact, even he struggles to list all current undertakings.

“Where do I begin,” he sighs.

There are so many: an animated series based on a true story, about five brownfields – environmentally impaired indigenous lands – but with a twist: they’ve been cleaned up with indigenous community support.

Or working with language programs, such as he’s done most of his professional career. “Before I came to Missouri, I worked at Cherokee Nation and did animations and worked as a language technologist with Google, Microsoft and Apple to get our language on all the different devices,” he adds. “Now our language is on every device, pretty much, which are sold in stores. I’m trying to figure out how to make sure that our language continues.”

He does this using Cherokee fonts that he created, more than 40 total. “These fonts were a new process in the beginning,” Erb says. “I don’t know if controversial is the right term, but obviously it was a concern in the beginning, whether or not new fonts were needed. Now they seem to be adopted much more readily. We don’t have the luxury of having thousands of fonts, so everyone you do is very important that you get it right and that people have some kind of input on them.” The fonts are in different Cherokee Nation language programs, and also shared with his community.

When in meetings with Apple and others, Erb brought the Cherokee Nation chief, colleagues, immersion teachers, children who spoke the language, and others with him to meet the corporate leaders.

“They took us seriously,” Erb says. “We are still one of the few indigenous languages that are installed [on Apple products]. Straight out of the box, for iPhone. That’s amazing!”

He’s also working on a VR – a computer-generated virtual reality, where a person interacts in a three-dimensional, 360 environment using electronic devices – funded through a grant from the National Science Foundation. Erb is working with Palmer on this planetarium project, Erb’s work involving the Cherokee Nation and a portable planetarium to take out into communities.

A former Cherokee Nation science officer, who did STEAM outreach in schools in Cherokee Nation, asked Erb: “Can you make an animation for this?’ And I thought ‘well, you know I do not do a 360-planetarium animation,’ but I thought I could figure it out, so I spent about six months trying to tell a story in that realm. When you make it a 360 environment unlike the traditional standard film, there’s a different kind of language because you can’t do the traditional camera shots.”

This was because it used a different film-production language and a different way of storytelling through the camera, Erb was not used to.

“It was hard. I didn’t have a lot of language skills when I was young. I could, you know, name animals and a few words, but it wasn’t enough. I needed to know more complex sentences and certainly Cherokee. Most people in my generation don’t speak much Cherokee.”

In addition, he recently completed an animation using the Cherokee language for a documentary called “Searching for Sequoyah” where he wrote the animated historical scenes of Sequoyah, a Cherokee person who wrote in the 1800s. A preview screening for the Tulsa Native American Society was broadcast Oct. 11, with a PBS Broadcast Premiere on Nov. 1. It is scheduled to appear on American public television on Nov. 21.

Another project: A Kanyen’kehà:ka Mohawk people piece in which he is creating a short, animated part of a larger undertaking. “’The Clay She Is Made Of’ is an animated documentary drawing comparisons between Sky Woman of Kanyen’keha (Mohawk) origin story and Kahstoserakwathe Paulette Moore’s mother - Patsy Hill. Sponsored by the Ontario Arts Council, the film focuses on the strength, humor and heart of Onkwehòn:we (Indigenous) women. Kahstoserakwathe Paulette Moore is a filmmaker and educator who focuses on the wellness of Onkwehô:we people through language, land and relationships.”

There are more projects where these come from: “Just a bunch of different things,” he explains. “Indigenous animators – there’s not that many and so it really keeps you busy trying to keep up with the work.”

He’s also done work for the American Indian Resource Center working with communities from Muscogee communities and Cherokee communities, teaching animation and film in the Muscogee and Cherokee languages, as well as producing film for the National Park Service.

“One of the things you learn fairly quickly – on any kind of project in the indigenous community, is it’s all consensus building, and involvement – and those are the long-lasting projects that are successful in communities when you are involving other people and decision makers. You certainly are consulting with a number of elders and talking to people about what you want to do before you do it.”

Erb says his interest in indigenous peoples began when he was in a computer-animated class in grad school while earning an MFA at the University of Pennsylvania with a concentration in Digital Media.

“My professor told us to tell a story, and all of a sudden, I thought I could tell a Cherokee one,” he says. “And that little idea turned into the rest of my life! And what this gave me was the ability to do something more connected to the community.”

After his MFA he fell in love with telling indigenous stories in digital media, he says.

Rabbit Stories 3D animated film series. Created, directed, and produced by Joseph Erb.

The Future

Erb says he has learned asking questions is more important than finding answers, as in asking questions one learns how to examine things in a different light. “It gives you more questions,” he says.

“Not that answers aren’t important, but learning how to figure the answer to questions, which creates more questions, is really the key, and that’s where I think these institutions, like Mizzou, are giving them the foundation of questioning things and finding out the next evolutionary step of understanding – in whatever field.”

His hope for the future is to learn more about his Cherokee culture’s language, as well as inspire other students or researchers to continue his work in translating indigenous words and languages so they are preserved and known about.

“I think narrative and narrative storytelling is where indigenous stories can be more fruitful and help society. We all are part of a larger thing connected to community and language and land and space, and why that’s important is that narratives [promote] understanding and will give a healthier understanding of story, which will help with the environment, the values of that, the values of place.”

He says that kind of understanding leads to tolerance of differences and connectivity among peoples.

“A good narrative shows that place matters, no matter where, and this can actually help and heal other environments. I think that narrative is actually one of the most important things in contributions that we can do for society, to build these archetypes and places that actually can transform society.

“When I’m old and in a chair and I think about what I did in my life, I’ll be pretty satisfied with what I’ve completed. So, if I didn’t make it another day, I can say I had an impact on my community. And you know, what I care about is that I could affect seven generations from now. That there was an impact. That I was able to do that.

“And I can say I contributed to it, and in 200 years everything that I made is important because it’s all in the language. They’ll study these stories, these animated films of these archaic little things and they’ll see how we spoke, and they’ll see our language, they’ll see what our buildings look like.

“I think though the only thing that makes me special is I’m a link in the chain of a bunch of special people."